Tucked away in a quiet corner of Mitte, a small group of eight- to ten-year-old kids are huddled around a projector screen. Before them, two teachers demonstrate how to make colourful animated dogs spin, jump, and walk ten paces forward, all through simplified code.

Words

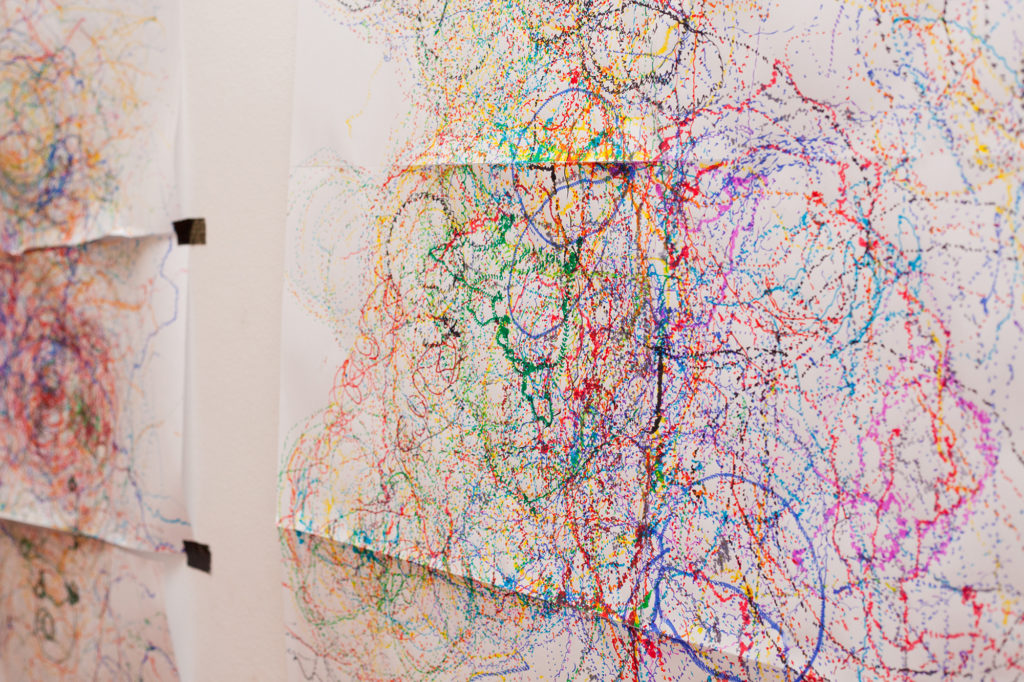

Photos

Valentina Culley-FosterIt’s mid-afternoon, and the kids are visibly tired, but have enough energy to shout out suggestions as to what the dog’s next move could be, aware that only certain blocks of code will fit together. Soon the demo is complete and the group divides up into pairs, each of which are given their own brightly coloured MacBook. Now, they will use the skills they just learned to work on their own video game that they will present to their parents in a few hours.

This is the last day of spring camp at Digitalwerkstatt, a German organisation that teaches digital skills to kids aged six to twelve, allowing them to understand the basics of the technology so present in their daily lives. This week, the participants have built robots, experimented with a 3D printer, made videos, and written code to make their own computer game.

‘Learning by doing’ is their motto, says Julia Eckhoff, Digitalwerkstatt’s Berlin project manager. ‘But it’s also important that the kids understand what they are doing.’ There is enough passive absorption of technology in their lives, she explains, and so the aim of Digitalwerkstatt is to empower kids to engage with it in a mindful way. Thus, they learn the basic vocabulary and applications of coding, some fundamental robotics, and even digital animation.

The work that Digitalwerkstatt is embarking upon is part of a worldwide initiative aimed at getting kids to start programming at a young age. ‘Don’t just buy a new video game, make one!’ President Obama famously quipped, and programs like Code.org and Girls Who Code are just some of the many organizations promoting digital literacy for the next generation. You can even find toys for toddlers that teach them the fundamentals of programming before they can even read or write. But is this just fun and games, or are we doing our kids a disservice if we don’t make sure they are as fluent in mapped programming concepts as they are in arithmetic? As technology becomes more and more prevalent in our daily lives, will those lacking knowledge of basic computing language be left behind in the future economy?

‘We have to educate the kids for a future wherein we don't know what is going to happen.’

‘We have to educate the kids for a future wherein we don’t know what is going to happen’ says Julia as we huddle together on the small children’s stools. ‘At the moment, we are educating them for a reality that is no longer there in a way, but the jobs we will do in the future … we don’t know yet what they will be.’

Digitalwerkstatt is a kid’s wonderland, with brightly coloured furniture, interactive toys, art supplies, and handmade projects decorating the walls and shelves. The animated dogs the kids are now working on were made using a program called Scratch, developed by The Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the MIT Media Lab to help kids learn the basic language of coding. Next, Julia shows us the robotics project that the students have created, a hardware sculpture resembling the insides of a computer. Earlier that morning, they had a family workshop for children aged six to seven. ‘Here’, she beams, ‘parents and kids learn together, which is really important because then parents really take the time to do something with their kids.’

Someone cries out, and Julia has to excuse herself to run and speak to a pair of boys who have gotten into an argument while playing at a laptop. This is the daily stuff of working with kids, and after a short pep talk, the dogs they’ve coded are dancing, spinning, and moving again, and the boys are laughing.

***

Digitalwerkstatt was founded two years ago by Verena Pausder, who teamed up with the Bavarian toy company HABA to create an organization dedicated to teaching kids the fundamentals of digital technology. The relationship with HABA meant that instead of writing bi-annual grants or spending precious time organizing fundraisers, Digitalwerkstatt could focus 100% on the kids. ‘The goal is to be self-sustaining’, says Julia. ‘It’s absolutely clear that this won’t be a cash cow, but that’s not the point.’

Though it might not be a franchise in the making, the organization has been growing fast. Their pilot programme was in Berlin, both at their space on Linienstraße and at the Facebook-owned Digitales Lernzentrum Berlin. After a year in Berlin, they opened a space in Munich, and since then they have opened in Hamburg, Frankfurt, and Lippstadt.

Digitalwerkstatt tries to reach as many children as possible by working with schools and offering private workshops and camps. They collaborate closely with institutions across the cities in which they are based, with both public and private schools booking regular sessions or one-off workshops. Digitalwerkstatt is responsible for the pedagogical content, lesson plans, and materials. This means teachers can relax a bit while gaining new insights on how to integrate technology into the classroom.

In the afternoon are the private courses, meaning the kids come to explore a specific theme such as coding, robotics, minecraft, or video production. On weekends and holidays, they offer three-hour workshops or, as is the case at the moment, week-long camps where kids can spend an immersive five days embarking on a plethora of digital experiments. Parents can even book a workshop for a birthday party or special event. The organisation also works with underprivileged communities, offering a 75% discount to those with a Berlin Pass 75%. Unsurprisingly, demand for the courses is high, and Digitalwerkstatt is always fully booked.

Julia has been on board from the beginning. Her background is in cultural studies, but she also studied education. Her passion for her job is evident in her every word: ‘I love helping people get along and be active, to solve problems, to be confident. This is my approach to really supporting the kids.

‘In my experience, it’s really good to have a team that’s committed to building something.’

Julia is also responsible for building Digitalwerkstatt’s team, which is comprised of pedagogues, game designers, coders, educators, and cultural theorists. Hiring instructors is particularly difficult, she explains, because they have to have both the technical skills and the ability to convey those skills to a younger audience:

‘It’s important for us when I choose the instructors that I see how they work with the kids, that they’re not just technically skilled, but are good at teaching. Of course they know a lot already, but they have to work with what the kids know. It’s not so easy to find people who are both interested in the pedagogical side of things and this interest in technology.’

The fixed team in Berlin consists of five team members and several freelancers. ‘In my experience, it’s really good to have a team that’s committed to building something’, she smiles.

***

Teaching programming to kids has become a trend these days, and it’s hardly a surprise. Many experts, including Bill Gates, see a bleak future for the job market in the coming century, asserting that robots and computer programs will likely be doing a range of the jobs many cling to for stability. Areas such as factory work and customer service have already begun to feel the losses, and the transportation industry is likely to be next. According to New York Magazine, by 2020, the tech industry expects to have a million more positions than it can fill. One good way to secure a bright future for our kids, many argue, is to arm them with the language of coding so that they can thrive in an increasingly digital world. After all, in a world full of robots, someone has to program them, right?

Even if not every pupil will grow up to be the next Bill Gates, the skills required for coding, principally computational thinking, could be valuable tools that prepare children to solve problems across their future professional and personal lives, argues Dan Crow in the Guardian. ‘Computational thinking’, he writes, ‘teaches you how to tackle large problems by breaking them down into a sequence of smaller, more manageable problems’. In the same way that theatre classes improve communication skills or science helps us understand and marvel at the world around us, perhaps coding classes could make us better, more efficient thinkers.

Cities like New York hope to offer every kid access to coding classes within the next ten years, and countries like Estonia and Australia already incorporate it into the national curriculum. But Germany has been slower to catch on to the trends in ed-tech. This is partly a funding issue, with schools being dependent on the local government for their budgets, but it is also an issue of culture and generation. ‘Especially in Germany, they are not so open to technology’, Julia admits. Sometimes, however, it’s that teachers simply don’t have the training needed to figure out how to integrate technology into their classrooms. Generational gaps and the primarily analogue education degrees in Germany mean that teachers, while they may be open to new ideas, lack the knowledge to bring them to their students.

For this reason, Digitalwerkstatt also offers teacher training, where instructors can come with their colleagues or individually to gather cutting-edge pedagogical tools to help their students absorb information in new and exciting ways. It’s not only about giving teachers the computers or tablets that they could use, explains Julia, it’s training them how to use them effectively: ‘Sometimes you see that schools have the technology there but they don’t use it. You need a concept, you need a plan for what to do with it.’

It is considered common knowledge that too much time in front of the television has an adverse effect on children’s brains, but most experts agree that the monitored use of tablets or computers is not harmful for children. Whatsmore, it’s an undeniable fact that the future will see more and more technological advances as children grow up, meaning that the sooner they grasp how to use technology for good and what its limits are, the better. Julia agrees:

‘It makes no sense to forbid it. Of course you need some rules or agreements, but we cannot avoid the topic. We want the students to, in an age-appropriate way, deal with the digital world. Because, in dealing with it, questions come up, we talk about it, have experiences, and this is the way you gain confidence and can learn yourself where the limits are. It’s not a given, you need the education.’

***

It is easy to see how much the kids love their experience at Digitalwerkstatt, and the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. ‘I’ve very often heard, “It was the best day of my life!”’ Julia exclaims. Although her job requires long hours and a lot of energy, the inspirational stories that fill her week are more than worth it:

‘A few weeks ago, one of our girls who comes on a regular basis to our courses asked to give a workshop on her own to her friends. Her mother said that a trainer could be there, but only as a backup! Of course we did it, and I found it so inspiring because this is exactly what we want: for kids to be confident and to showcase what they can do.’

This story is especially moving given the current gender disparity in the world of tech, with even giants such as Google boasting only 30% women across its worldwide staff. Discrimination concerns aside, there is certainly a cultural component hindering girls from embracing an interest in technology, and the reality is that there even at Digitalwerkstatt, more boys register than girls. ‘We really have to fight against it’, Julia admits when asked about gender disparity in the organisation. To combat this stigma, they offer international girls day and the occasional free workshop for girls.

‘Because we work so much with schools, we really see how interested the girls are, how excited about the work they are. Their gender is not the reason why they aren’t participating. With boys, I notice that parents will enroll him for everything, but with the girls they are a bit more hesitant. They don’t trust this interest somehow.’

When asked whether she thinks that the future will see coding integrated into the curriculum in Germany, Julia smiles. ‘It’s a hard question’, she admits. ‘I think what students should get is a basic understanding of what’s needed to program. There are a lot of languages and they don’t need to learn all of them, but I think what’s important for our society is that they know the processes behind the technology. Because otherwise, you are just a passive user.’

The primary goal for Julia is that technology is seen as a method to enhance the education process, rather than a distraction or danger. ‘It is important that we use technology as a tool for learning and teaching’, she asserts. ‘There is a lot of potential there and I think we should open ourselves up to it.’ Demystifying digital tools also helps to empower kids to understand their limits. When you have a good understanding of what technology can do, you also get a better understanding of what it can’t do, or shouldn’t do.

‘It is important that we use technology as a tool for learning and teaching.’

In terms of future plans, Julia says that Digitalwerkstatt has so many new ideas that they can hardly keep up. One of them, she says, is expanding their reach to schools further away. For this, they are working on a bus that can travel to schools in Brandenburg, and which would serve as the classroom for the workshops. Outside of that, the team itself is constantly trying to learn new things, keep up on trends, and integrate new technology into their process. ‘With everything we do, we learn’, says Julia. ‘After two years, we know a lot more than we knew then, but it’s a process.’

It’s 3.15pm and the children are gathered around the projector once again, this time with their parents at their side. The teachers give a final presentation of what their students have done this week, complete with a dynamic video showing all the projects in process. Then it’s time for the kids to receive their certificates, and the room erupts into applause as the students march, one by one, to retrieve their awards. They’ve completed a week of digital adventures, and realised a series of inventive projects. And maybe, in addition to that, they’ve taken another step towards becoming one of the technical visionaries of the future.

For more information on Digitalwerkstatt visit their website.