With his thoughtful essays and deeply reported magazine features on the trends and tastes that have dominated the past decade, Kyle Chayka has become one of the most interesting chroniclers of his generation.

Words

Photos

James ChororosIf you happen to pass by Sey Coffee, the latest hip addition to Brooklyn’s former working-class neighbourhood of Bushwick, you may notice that the room is filled with under-40s bent over their laptops. Many of them will be freelancers, and chances are that Kyle will be among them.

In recent months, he has usually spent his mornings here, under the airy skylight and among the succulent plants, flat whites and semi-industrial furniture that characterise this café, as so many others.

Kyle, a 30-year-old from New England, works freelance in New York’s media industry and could, therefore, pass for most of his contemporaries at Sey Coffee. But unlike most of them, he doesn’t just consume the coffee, atmosphere and aesthetics of Brooklyn anno 2018. He might be researching an essay, a book or a magazine feature about the place – and time – that he is at. Kyle has marked himself as one of the most thoughtful chroniclers of his generation.

Whether he is writing about how cafés all over the world have begun to look alike, why people who have it all pursue the minimalist gospel of having nothing at all, or how the lifestyle magazine Kinfolk has dominated the design and aesthetics of a decade, Kyle usually turns his mind and pen to topics in his hemisphere.

‘I wanted to reflect on my own experiences, however mundane they might be, and write about what surrounds me every day. The way we live and work is the way we live our personal lives and exist in the world, and that is what interests me,’ says Kyle.

When he left New England for New York in 2010, having gained a degree from Tufts University in international affairs and art history, he started out as an art critic. The thinking of those who he met in that world helped Kyle train his eye to the crossover between culture and the individual.

‘I wrote a lot of museum and gallery reviews, and artists, who tend to be very smart, don’t see a barrier between cultural things and our lives. That made me think about how the way things look and how particular trends spread, and how you can analyse your time by looking at design, art and the visual world in general,’ Kyle says.

Kyle soon started writing about the things that he mulled over during his days spent at coffee shops, co-working spaces and restaurants in Brooklyn. Some time between 2015 and 2016, when Kyle was travelling through Scandinavia, he began to pick up on a trend that he would end up writing several articles about.

Although he was travelling through countries far from home, the Airbnb apartments, eateries and co-working spaces had begun to look eerily familiar. In fact, the world had begun to look a lot like Brooklyn.

‘I’d been travelling quite a bit, and particularly in the Scandinavian countries I started noticing that the aesthetic was the same as the cafés I was seeing in Brooklyn. As a freelancer, I spent a lot of time in coffee shops, but it wasn’t just there that I saw this very generic, streamlined design aesthetic. Airbnb apartments I stayed in around the world also looked alike, and they shared the aesthetic of the coffee shops. That was when I started to think about the concept of “AirSpace”,’ Kyle says, referencing the term he coined and would go on to write a much-discussed essay about for The Verge.

‘My idea is that we’re in a permanent state of interconnectivity.’

The term AirSpace does not just refer to a specific style, such as the concrete floors, exposed brick walls, Edison light bulbs and industrial furniture that were en vogue when Kyle wrote the essay. Instead, it refers to the way that style spreads across the globe. All of a sudden, thousands of owners of cafés, Airbnb apartments and co-working spaces seemed to desire the same design aesthetic, and Kyle became convinced that it wasn’t a coincidence. He felt sure that the current style, which can be described as airy minimalism, would be replaced with another trend that would spread as far globally, and that the new trends would spread the same way.

‘My idea is that we’re in a permanent state of interconnectivity. Right now, the style is this airy minimalism that’s particularly associated with millennials, but it’ll be the same in the future, just with a new aesthetic – people will go on appreciating the same things. The style might change, but the communal nature of the desire and the globalised scale of it won’t change, it will only increase,’ predicts Kyle.

The current style and the way that it has spread around the globe has been blamed on millennials, but they’re just the first generation to live in AirSpace, according to Kyle.

‘I don’t think it’ll go away with millennials – in fact, I think the trend has only become more intense in the years since I wrote the essay,’ he says. ‘What we see is hype culture supplanting local identity, and I feel like the AirSpace argument is that what you see on Instagram trumps the local, organic style.

‘Paris is one example where you see the clash or the differences between the old world, where aesthetics were sourced locally, and AirSpace, where aesthetic is something global – you have the old, traditional brasseries, which are the definition of classic French style, and a wave of hipster cafés that look more like the cafés you see in Brooklyn or on Bali.’

Although airy minimalism has become so popular that it can now be considered mainstream rather than hip, it’s still going strong. Kyle believes the next design aesthetic that will spread throughout the world via AirSpace will be softer and messier, inspired by the US West Coast in the 1960s and 1970s.

‘So far we’ve seen a focus on the minimalism of the 1950s and 1960s, and I think this more bohemian style will take its place – at least that’s what I see becoming popular right now. We’ll see more woven rugs, tanned leather and even more plants, and less sterile minimalism.’

‘AirSpace was born out of social media and the predominance of the visual internet.’

Kyle has some ideas to explain the fact that more people have begun to desire the same design aesthetics. ‘My theory is that AirSpace was born out of social media and the predominance of the visual internet. It hasn’t been that long since the social media networks began becoming more focused on multimedia – as opposed to being text-driven – but it’s already changed the world,’ he says.

Flickr and Pinterest were early examples of visually driven social media platforms but, according to Kyle, it was Instagram that made visual communication more mainstream.

‘We all have iPhones and with it this camera to stick in the world, and you can keep up with the visual aspirations of people from all over the world,’ he says. ‘Social media makes taste and trends spread faster, and that’s why you see people from all over the world cover the same aesthetics.’

It’s a sad truth for a writer, Kyle admits, that inspiration, taste and trends spread faster when they’re communicated visually rather than verbally or in written form.

‘The cynical part of me suspects that people never liked to read that much, because reading is a hard, active process of trying to understand something. Images, on the other hand, communicate immediately. As the structure of the internet has gotten better, so that it can handle more imagery and more multimedia, it has become increasingly visual. So has the way we communicate – many people send emojis or GIFs rather than text to one another. Visual culture has become the most mainstream culture.’

These days, Kyle tends to sleep in, probably too long, he admits. Then he heads to somewhere like Sey Coffee for a morning of emails before he has lunch in the neighbourhood. His afternoons are spent in the heart of BedStuy at the co-working space Nowhere, which was founded by a travel writer in an empty warehouse and is close to Roberta’s, the hip pizzeria that helped put the area on the map for millennials.

When Kyle travels, he often stays in Airbnb apartments; he is fully aware that he’s a consumer of the trend he has been describing, and critiquing, in his writing.

‘The story of Williamsburg over the last 20 years is the story of aesthetic gentrification. You had all of these broken-down factories and empty industrial waterfront spaces that became the cultural hipster centre of the States. Now Williamsburg is pure AirSpace, and I feel partly responsible. I’ve lived in this part of Brooklyn for close to 10 years, and I’m one of the people who’s consuming the AirSpace version of Brooklyn,’ he says.

‘I’m not sure if the spreading of AirSpace is a problem per se, but I’m still trying to come to grips with it. It’s a thing that is happening and a permanent state that we’re entering where everything is becoming more homogenous and less diverse.’

Or flat, you might argue. To Kyle, AirSpace is a continuation of Thomas Friedman’s seminal work The World Is Flat, an analysis of globalisation in the 21st century. ‘It’s common knowledge that we’re more interconnected, politically and economically, than we’ve been before, and now this flattening is happening culturally and aesthetically as well. I don’t know if it’s a problem, but we should be aware that it’s happening.’

The one aspect of the flattening that does seem problematic to Kyle is that the world of AirSpace might be global, but it isn’t available to everyone. ‘The homogenised aesthetic reflects the need of a special socio-economic class, and one of relative wealth. It’s a very mobile, very rootless group of consumers who like to have an availability of co-working spaces, good coffee and good WiFi wherever they go. The needs of that hypermobile class can surpass the needs of local populations, and that’s a new kind of gentrification,’ Kyle says.

‘AirSpace has this particular infrastructure of cafés, co-working/living places and Airbnb apartments, and it’s growing all the time. These days, you can choose to travel to a place to be a remote worker without wanting an authentic local experience.’

He says that this is different from the old-world experience of travelling to hotels. Hotels might be generic, but you leave the bubble once you step out of them instead of hopping from co-living space to café to yoga studio when you remain inside the AirSpace bubble.

Kyle considers digital nomads and remote workers, with their need for convenience in order to get work done, the priests of AirSpace. ‘Wherever you find remote workers, you see the same cultural icons.’

Kyle has lived the digital nomad lifestyle for shorter periods of time when writing about the movement, but although it was convenient and comfortable, he missed his home in Brooklyn. ‘As much as I believe in globalisation and the AirSpace ideal, there is still a specific place I want to be.’

For the past year or so, Kyle has focused less on the magazine features that he has become known for and more on a book. It will be published by Bloomsbury in early 2020 and the idea came from an essay that he wrote for The New York Times on the oppressive gospel of minimalism.

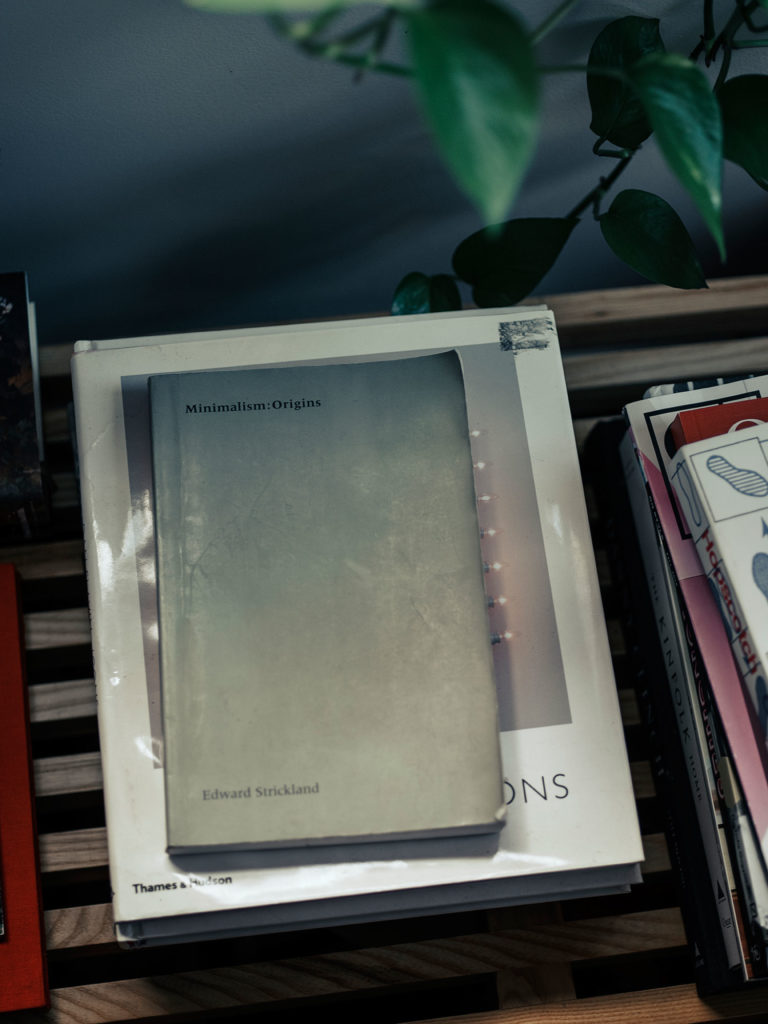

‘It will be a short book about the history of minimalism and about why people are so drawn to this emptiness and absence of things. The book looks at various areas, everything from lifestyle, philosophy music, zen aesthetics and art and architecture,’ Kyle says.

The book has mostly been written in cafés and co-working spaces, but this is one of the only ways in which the writing process resembles the writing of his magazine articles. When he gets to work on his next book, which will be about the influence of digital culture in the real world, it will likely be written from Brooklyn cafés too. And although the changing aesthetics of these businesses will most likely have been transported to the rest of the world via AirSpace by then, Kyle Chayka will still be there to chronicle the contemporary and his generation’s way of living.

Keep abreast of everything Kyle is up to via kylechayka.com