Many people might think that Van Bo Le-Mentzel is a dreamer, and he would agree. What does he dream of? A more sustainable, less capital-driven world in which people reactivate and share spaces. Through Tiny House University, Van Bo and his team are making this dream a reality.

Words

Photos

Robert RiegerA little over a year ago, a cluster of small, house-like structures appeared in front of the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin, next to the Landwehr canal. They soon began to multiply, as did the number of people working, studying, cooking, and sleeping there. These stylishly designed buildings, measuring less than 10 square metres, formed part of the Tiny House University Collective, a Berlin-based NGO founded by Van Bo Le-Mentzel, a Berlin-based architect and DIY activist, with the goal of creating new models of social neighbourhoods.

The tiny house movement is a social initiative geared towards downsizing the spaces we live in. It originated in California, with its first pioneers creating alternative living structures in the 1970s. Any free-standing residential structure less than 46 square metres is considered to be a tiny home.

The movement is increasingly popular all over the world, especially in places where people are looking for lower rents and a more sustainable living situation, such as the USA, Japan, the UK, and Germany. Van Bo’s theory is that the tiny house origin story is related to the advent of Silicon Valley, where computer geeks profited from close quarters by building computers, and communities, in their garages: ‘Because a garage is 10 square metres and close to the street, people can come by, share ideas, find each other. It’s a social scene. If it had all happened in backyards, it would have stayed hidden. So I call these “spaces of possibilities”!’ Van Bo surmises. He has a calm air about him, and is characterised by a soft-spokenness and dreamy nature. But despite this, he is an organiser, and always manages to make things happen, and find the right people to collaborate with to make his dreams a reality, with Tiny House University being a prime example.

‘We want to reactivate spaces and make neighbourhoods better, to improve social potential!’

Tiny House University began in 2015 when Van Bo started the project with a group of refugees who had just arrived in Germany. Van Bo noticed them queuing in front of LAGESO (now LAF), the State Office for Refugee Affairs in Berlin. ‘It was packed with people – two, three, four hundred a day – usually waiting there from the night before to make sure to get a number,’ explains Van Bo, who himself came to Germany as a child refugee from Laos. His migrant background informed his decision to get involved with various refugee integration initiatives, and upon talking to the refugees at LAGESO who were frustrated after realising that the office could offer them no assistance, he decided to take matters into his own hands. ‘My idea was simply to build something together with them; to help them.’

Van Bo has a track record of taking charge and leading DIY projects to success. As a young and unemployed architecture graduate, he felt the need to do something more practical, and so completed carpentry training at the Volkshochschule in Berlin. Soon after, he designed a furniture set that was easy and cheap to make, which provided the basis for his 2012 book Hartz IV Moebel: Build More, Buy Less. The book inspired a grassroots movement of people building their own furniture instead of simply hitting IKEA, and his designs now represent the core furniture of tiny houses worldwide. Van Bo has been the initiator of many inspiring crowd-funded projects. He has designed fair trade shoes, the Karma Chaks, taught at the University of Fine Arts Hamburg, and, in the process, has built up a support circle that will stand behind him whatever his ideas are.

His multifaceted career helped Van Bo to bring the idea of building something with the refugees he had met to fruition. After assembling a team of refugees eager to help, he gathered discarded wood that he’d found on the streets and turned to the ‘Konstruieren statt konsumieren’ Facebook community to ask for tools. This is how the first tiny house was born. ‘We called it “Hotel LAGESO”,’ he laughs.

***

We are sitting in the latest tiny house at the Bauhaus Campus. There are 13 buildings at present. The number grew rapidly as more and more people got involved in the movement. ‘We started building tiny houses in gyms, where the refugees were staying,’ Van Bo tells us. ‘We soon teamed up with Syrian, Egyptian, Iraqi, and many African carpenters and helpers, and I realised how much I, as an architect, could actually learn from the refugees, people living in mobility. So, we started designing new kinds of apartments, no bigger than 10 square metres, and we just put them on car trailers so they could stand in parking spots.’ He calls the structures ‘100-euro apartments’ as it is stipulated that the rent cannot exceed 100 euros.

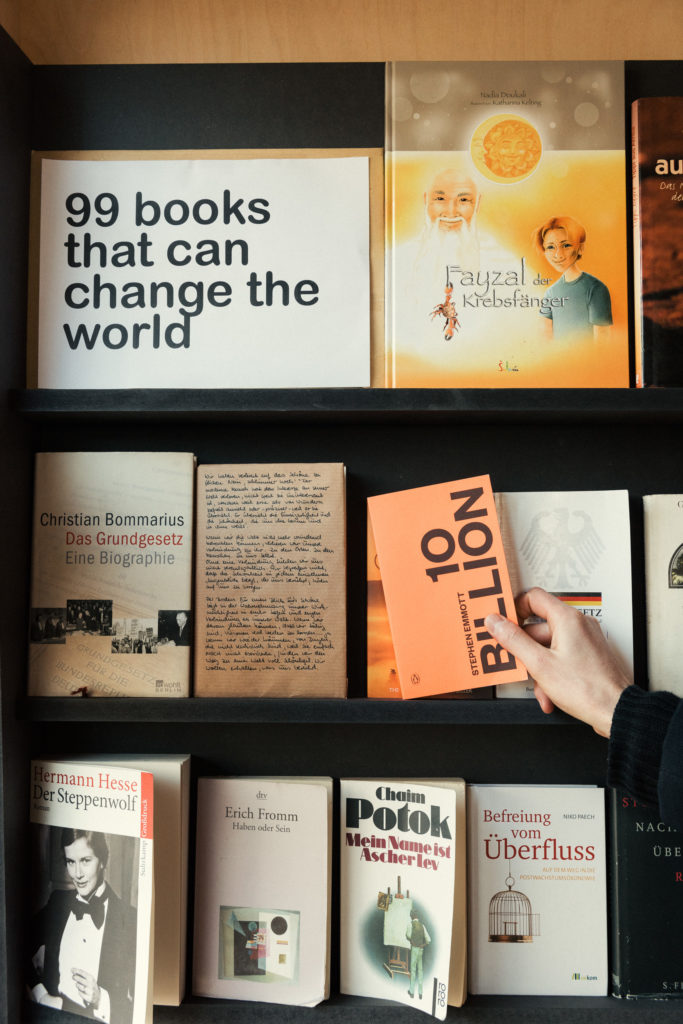

Van Bo is keeping himself busy as we talk, assembling and rearranging furniture in the tiny structure. The sun is setting and it’s getting chillier, so he turns on a gas heater that quickly warms up the small house. Downstairs is a tiny kitchen, a living/working space, even a flat-screen TV on the wall, and upstairs is space for a cozy bed. All the houses located at the university – the café, the library, even the public toilet – are designed in a way that one could actually sleep in them.

For Van Bo, the project is a way to rethink how we live together. ‘With the tiny houses, we can experiment with a lot of ideas! One of them is, of course, housing. How could we organise a society in a post-migrant, post-colonial, post-democratic world? What’s next?’

‘How could we organise a society in a post-migrant, post-colonial, post-democratic world? What’s next?’

Outside, about half a dozen people are busy peeling and chopping vegetables. Their work is visible through the huge windows of the structure in which we sit. They are preparing a dinner at the Holy Food’s House, one of the buildings designed for catering. The food is prepared using only discarded and donated ingredients, and the dishes will be offered to those in need. Tonight there will be a community dinner celebrating one year since Tiny House University opened at the Bauhaus-Archiv.

Many of the volunteers and members have spent some time sleeping in the houses, too. Van Bo welcomed people to stay – whether they were refugees, homeless, or one of the interns – as long as he could trust them to leave by 9am when the Bauhaus museum opened its doors. Van Bo tells us that Tiny House University also hosts many events, lectures, and dinners, and provides a platform for people to meet and work together, and to become friends.

***

Now, several weeks after our meeting in the cozy 10-square-metre living quarters, the tiny houses are leaving the Bauhaus campus. Some are making their way to Wittenberg, where a new community will soon spring up. ‘One of our members, Apo, is a Kurdish guy; a displaced person. He’s been very active with us and now he is starting a new community in Wittenberg. We will put our house there and we are inviting people to join us. An Israeli guy, Noam, is setting up a workshop, helping people to build their own tiny houses. It’s so interesting to watch the ideas and the utopian steps of a person who is not even “supposed” to be here, who has no rights, no papers, starting all this in a town where Martin Luther wrote hate speeches against Turks and Jews. These are things I find very important: to confront people with their own history and evoke changes.’

In addition to Wittenberg, some of the other houses will move to Holzmarkt, the experimental urban development area in Berlin. Here, a third person, Amelie, will curate the project. Curate is the operative word because, while tiny house communities don’t have leaders, someone needs to take responsibility for the goings on, advocate for the project, set the theme of the community, and set some boundaries.

Van Bo finds it important to always have one person in charge who has an overview of things, especially given the wide variety of people who congregate at Tiny University: ‘Every one of our new spots is a new core of people and ideas, all sorts of people. I think this differentiates us from the Bauwagen (container) communities. They are usually looking for like-minded people. Here at the Bauhaus campus, we’ve had homeless people, alcoholics, ministry workers, company owners, gay people, straight people, terminally ill people, pregnant women, Jews, Muslims. It’s a very nice cross-section of our society, which is not something you’d see in a Bauwagen community. That’s a like-minded bubble, which is totally fine but we don’t want to create bubbles, we want to reactivate spaces and make neighbourhoods better, to improve social potential!’

The biggest challenge tiny house owners face, especially in Germany, is that one cannot legally live in a tiny house. German law stipulates that every resident must register their place of residence, but that this cannot be on the streets. However, Van Bo explains, you also can’t live in your garden as it constitutes a place of leisure, nor can you live in Schrebergärten (small garden ‘allotments’), even though sometimes people still do. By extension, a tiny house that you can set up anywhere also cannot, in legal terms, constitute a place of residence.

Despite its obvious difficulties, Van Bo has high hopes for the tiny house movement. He dreams that ‘one day there will be a big enough, critical crowd who will show how tiny houses can help the community by sheltering, doing dinners, providing kitas, doing things that the government is supposed to take care of but cannot.’ He envisions a world where tiny houses can contribute to humanitarian causes, taking some weight off the government.

‘I think they will see how society reacts to the tiny house movement and they will realise that there is so much more behind it!’ he exclaims. ‘We, for example, have a library and a public toilet where we recycle waste. There are so many things that one could do for the community. What would happen if we defined living in a city as a contribution to society? I think everyone who owns something has a responsibility and they should offer what they have to society. Let that be property, or a tool, or knowledge. If everyone would offer something to one another, there would never be any wars again.’

***

‘What would happen if we defined living in a city as a contribution to society?’

Back at the Bauhaus campus, sitting in a tiny house creates a warm and homey feeling. It’s easy to imagine packing a suitcase and hitting the road with the tiny house on wheels. And this is exactly what Van Bo dreams of. ‘I hope people will realise that it’s better to buy or build themselves a tiny house instead of having a car, or a real house in the suburbs, because they will start to commit to the world and stick to the global ideas of the world. They will travel a lot, and if you do that, you don’t need a big apartment.’

This sustainable way of living, utopian as it might sound, is becoming a reality for much of the population, Van Bo tells us, with an ever-growing group of ‘urban nomads’ who populate the city landscape. Rather than defining themselves through possessions or property, they are characterised by their free spirit and respect for humanity. Could this be the next lifestyle revolution? Our host certainly thinks so.

Van Bo sees the future as centered around community. Luckily, he is already surrounded by many like-minded dreamers and supporters who also want to change things for the better, and to live in a less capitalistic society where it doesn’t matter where one comes from. He maintains hope for a brighter future, especially when he looks at his two young children.

‘My wish for my two children is that they keep their curiosity and their faith in laughter as long as possible. It is always a very nice moment for me to see them having fun, playing around, making something out of nothing: how they create their own toys and stories in their brains. That’s a really great ability and skill if you can just create something out of nothing. Some call it magic. And that’s something every human being can do when they are little, but then we lose it because people tell us that there is no magic. What I would really like is to create spaces where people can stay magicians, or reactivate their magic geniuses. Spaces of possibilities.’

Keep up to date with the activities of the Tiny House University via Facebook.