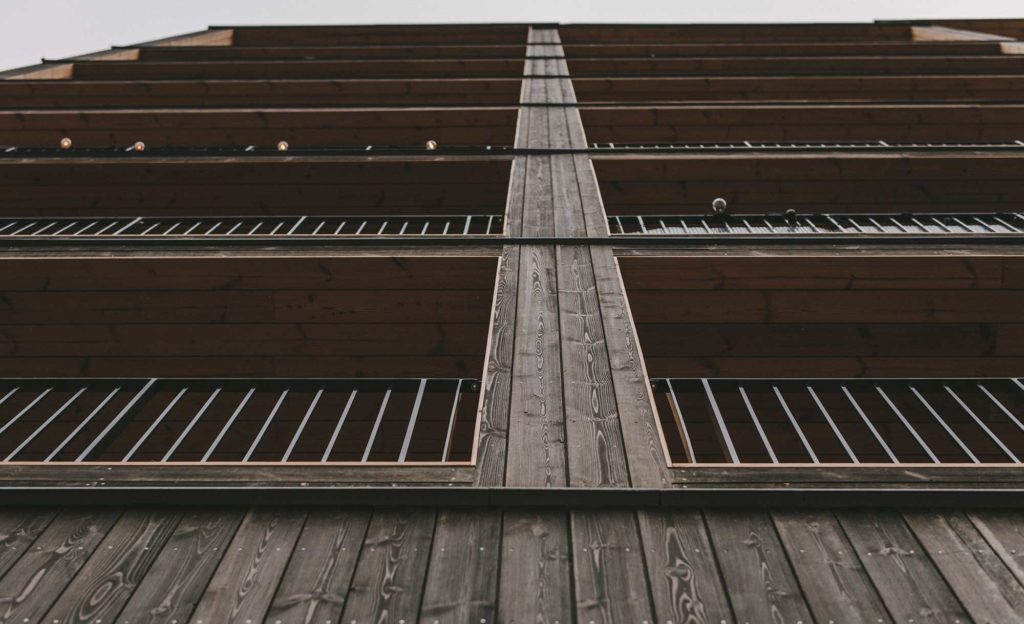

Imagine a construction site. Remove the noise, the clutter and the junk. Imagine that half the standard amount of workers complete the job in half the amount of time. Imagine that every part of the building can one day be picked apart and repurposed. Imagine no more – this is the reality when the Scandinavian architectural firm C.F. Møller builds a nine-storey residential house entirely out of timber. And according to the architect Ola Jonsson, industrial technology has the potential to spark a renaissance of wood.

Words

Photos

Elisabeth IngvarHe takes off his red woollen hat, looks over at the photographer and asks: ‘Do I have hat hair now?’ With his plaid shirt, matte beige glasses, and rolled up construction plans under arm, Ola is the quintessential Stockholm architect.

He is also an associate partner at the international architectural firm C.F. Møller, where he has worked for a little over a decade because of a shared passion for sustainability and innovation. Creating projects that are in harmony with the environment has always been a primary driver for him as well as finding an outlet for the pioneer within. ‘My dad was an inventor. I was going to be an inventor but they’re unwilling to call me an “inventor” at the office, so I became head of innovation.’

‘They’re unwilling to call me an “inventor” at the office, so I became head of innovation.’

Building houses from wood is hardly novel. In Sweden particularly there has been a long history of using wood for small buildings and homes. But industrial wood technology will create a resurgence in demand for wood, according to Ola: Lumber is reborn with the possibility of multi-storey buildings with walls, slabs, elevator shafts and stairwells made entirely of cross-laminated wood. Ola opines that we are living in an era where it is vital to use sustainable materials. In essence, he believes that this is where architects can have an ethical impact. This is what drives his passion for wood.

Ola places heavy emphasis on using renewable and bio-based materials that are also durable, with a long life cycle. Emissions are delayed for the length of this cycle as the wood itself, along with surrounding greenery, absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. And if a building is going to be demolished, the material can potentially be used for a simple building or building product, when it may then be turned into fibre-based products such as textiles or paper before it is finally used as biomass or burnt for energy. Lasting for hundreds of years, this long life-cycle chain delays the emission of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, thus positively impacting climate change.

Furthermore, C.F. Møller sources material from Swedish manufacturers who harvest wood from local, sustainable forests. This means that for every tree cut down, several more are planted.

‘Sustainability and life-cycle achievements only make sense if we make holistic changes on a large scale and imagine the effect over a long period of time,’ says Ola. ‘To achieve national and international climate goals, the building industry needs to change its course radically. Prioritising sustainable building is crucial, and is also a simple move that will have a great impact. One house doesn’t necessarily make a difference, but Sweden can have an inspirational influence on other countries, regardless of its small footprint on the world.’

Ola is an influencer in his own right. He is gearing up to visit China to lecture on solid wood and recently did the same in New York. He plays a key role in a multi-disciplinary research group exploring the benefits and disadvantages of building multi-storey houses with solid wood. The research focuses on how to meet technical challenges and legal requirements. And therein lies the renaissance, according to Ola.

‘People’s first response to wood construction is usually: “What about fire?” Yet buildings in wood are designed with the same regulations as all other buildings, and tests actually show that it’s safer to be in a solid timber building compared to concrete and steel. Still, it can be problematic getting the insurance companies to understand, potentially raising the insurance premiums.’

The house that Ola has designed is to be part of Kajstaden, a newly established residential neighbourhood in Västerås, a city in central Sweden. It is meant to simplify sustainable living for the community. Within Ola’s building there is a dedicated ‘cool room’ for storing groceries that have been delivered. This is designed to reduce car travel and eliminate the hassle of shopping for time-poor residents.

The first residents have started to move in and Ola is particularly happy to see lights giving life to the building. Homely, outdoor furniture and colourful adornments provide clues to the personalities of the residents.

‘With access to today’s industrial methods of building with wood, architects and engineers have few limits when it comes to designing,’ says Ola. ‘Kajstaden is a straight-up housing concept with a focus on the qualities of living next to the sea and in a sustainable manner. Pushing the limits of its capacity and building tall buildings is not the primary focus; what’s more important are the possibilities when it comes to using materials that can help to fix environmental issues, and the inspiration that Kajstaden can provide to future projects conducted by other developers.’

Ola refutes any suggestions that building with wood is more expensive. He says that the material is faster and simpler to put together, particularly as it is lighter, requires fewer lifts with cranes and more can be loaded onto trucks. He estimates that you can fast-track the build by up to half a year. ‘Time is definitely money in this industry. It’s cheaper to build in wood if you know what you’re doing.’

‘To achieve national and international climate goals, the building industry needs to change its course radically.’

On this particular project it took three workers an average of three days to build a single storey of the building – a rapid pace by any measure. ‘The team have said they don’t feel like building in concrete any more. Building in wood implies a quiet work environment, and a dry one too. In principle, you only really require the use of two items: a screwdriver and a screw.’

C.F. Møller, headquartered in Aarhus, Denmark, is one of Scandinavia’s leading architecture firms and Ola has played a key role in establishing its Swedish office in Stockholm. Being a fan of workplace diversity, he has recruited employees of varying ages from all over the world. This has created a melting pot of different ideas, providing innovative architecture as a reflection of society. Workplace equality is another focal point for Ola and C.F. Møller, and its Swedish office has a balance of female and male staff, at all levels.

Ola attributes much of his artistic approach to architecture to his time spent studying and working in Denmark. He believes that there is a more practical approach in Sweden, but that Danish culture encourages greater creativity. When C.F. Møller presented a talk on its project in Västerås, hundreds of people attended. It was explained why this building is well worth getting excited about. As trees absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and timber used as building material will as well, houses built from timber mean that a neighbourhood joins the forest in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

‘If all new buildings and city planning focused on timber, it would have a tremendous impact on quelling the harm caused by the release of carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere,’ enthuses Ola. ‘Wood provides great potential from an extended life-cycle perspective and is fundamental to the goal of a bio-based, circular economy. It’s a vital time for increased awareness within the building industry. We now have the technology and know-how. There are no excuses. I want to be part of eliminating the apprehension of other architects and builders and inspire them to join the renaissance of wood!’

For more information about C.F. Møller visit its website.